Regarding the topics of the true origins and purposes and messages of the collection of texts now commonly styled the Old Testament or the Tanakh, categories which include the so-called Five Books of Moses, I would assert that we cannot even begin to arrive at a viable conclusion until we have familiarized ourselves with and carefully considered the long and complicated and to most rather surprising real history of the so-called «Hebrew» alphabet.

(The present versions of the «Pentateuch» should probably be viewed as pseudepigrapha, or as belonging to the same category as the Corpus Areopagiticum, for example, formerly thought to have been composed in the first century A.D., by the Dionysius whom «Paul» allegedly met with, but now known to have come into existence only some 500 years later, and to have been written by someone intimately familiar with Proclus’ interpretation of Plato)

Much of this history has in fact been known to at least parts of the academic world for a very long time — hundreds of years, in fact — but, like so many other somewhat complicated and disconcerting realizations, it has not really been picked up by the wider public.

Very simply and briefly put, the present «Hebrew» alphabet, i.e. the one consisting of the somewhat «square» and quite beautiful letters familiar to people today, is not actually the ancient «Hebrew» alphabet at all, except in the sense that it was adopted by the group later usually equated with the «Hebrews» during or after the famous exile in Babylon — the present «Hebrew» alphabet is in fact identical to, or virtually identical to, the ARAMAIC alphabet, which was a very unexceptional alphabet used all over Mesopotamia and the Middle East during the last few centuries before Christ.

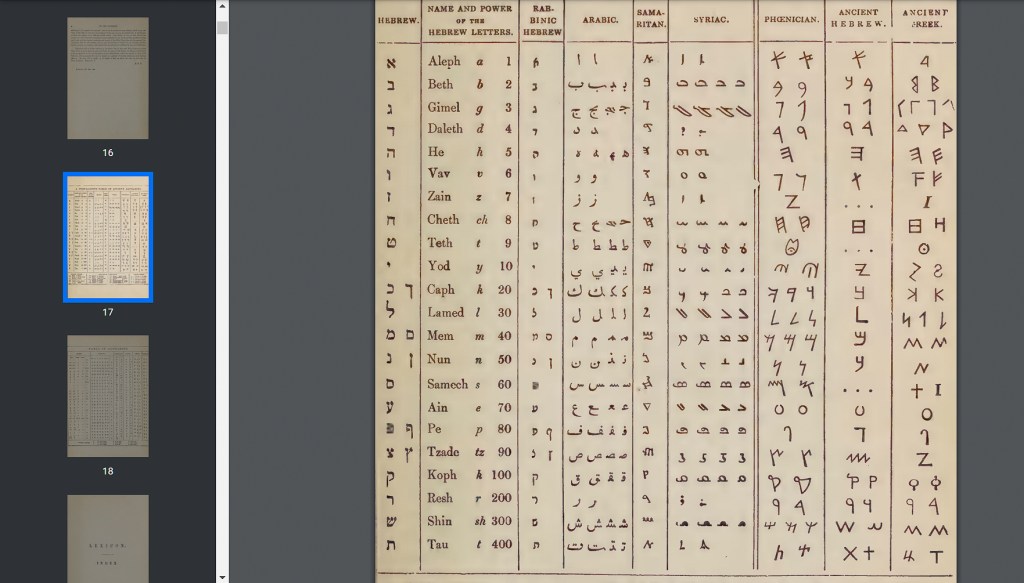

The truly ancient «Hebrew» alphabet, the letters of which had a very different appearance — please see Gesenius’ table (image) — is known to have been in use about 2600 years ago, but gradually fell out of use during and after the decades spent in Babylon.

Moreover, this «Paleo-Hebrew» alphabet is, as might surprise some, is virtually identical to the ancient Phoenician alphabet. In other words, there is no substantial difference between the ancient «Hebrew» and the ancient Phoenician alphabet, for the simple reason that both the Phoenicians and the «Hebrews» belong to the same ethno-religious group. There are very few, if any, scholarly and objective grounds for distinguishing sharply between them. According to some modern scholars, including some Israelite ones, the reality is that they were all «Canaanites» — probably with some Egyptian and other admixtures. The Hellenes of Plato’s time viewed them all as Phoenicians or Syrians.

One can see how this alone might raise many questions among the uninitiated.

It is true that the Aramaic alphabet, which, as already stated, also became the alphabet of the «Hebrews» at some fairly late stage, is based on the Phoenician alphabet, being a development of it, and that the Aramaic alphabet therefore has the same roots as the Phoenician-Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, BUT — and this should be food for thought — if the personage styled Moses or Moshe (an Egyptian name) ever existed in reality (was he the Akhenaten who vanished, or a relation of his, perhaps?), some 3,200 to 3,500 years ago, and that person composed written texts, those texts would have been written in either the Paleo-Hebrew/Phoenician alphabet, or, perhaps, in Egyptian letters or glyphs, and they could certainly not have been written in the later Aramaic alphabet!

You can probably see where this leads.

Since we have no ancient manuscripts or inscriptions (or at least no publicly available ones) containing passages from the texts now styled the five books of Moses WRITTEN WITH PALEO-HEBREW/PHOENICIAN letters (except for some tiny fragments, maybe) the present canonical, written Torah cannot be said to have any clear connection to Moses, nor to the millennium in which he may have lived, since the present texts have none of the letters Moses would have used.

I only came to this startling realization after about two years of studying theology, because so many modern scholars are avoiding the use of plain language.

Yes, we could conceivably posit a continuum of some sort between Phoenician/Paleo-Hebrew and later Aramaic letters, but any treatise which ascribes the kinds of elaborate and esoteric meanings now commonly ascribed to the letters of the Aramaic «Hebrew» alphabet, including the numerical ones, and which then uses these meanings in the interpretation of the Torah/Tanakh, without discussing the fact that any Moses of 3,300 to 3,500 years ago could not possibly have used those Aramaic letters, fails to prove much as far as interpretation is concerned, since one would first have to show that the letters of the ancient Phoenician-Paleo-Hebrew alphabet ALSO had such meanings, and that these were later transposed onto the Aramaic ones.

But it gets even more surprising. Paleo-Hebrew, and presumably Phoenician as well — they are really the same, as we have seen — were preceded by an ancient and very primitive script now styled «Proto-Sinaitic». This script was first discovered on some rocks in the Egyptian desert back in the 1800s, I believe, and seems to have its roots in the era when people up in Canaan/Palestine/Phoenicia began moving into Egypt, where an ancient high civilization was already in existence, some 4,000 to 3,800 years ago, in search of job opportunities and such like. Some became Egyptian mercenaries, others became laborers in Egyptian mines, and so on and so forth. At some point, someone invented «Proto-Sinaitic», by greatly simplifying existing Egyptian glyphs.

To say that the Phoenicians invented the alphabet, on the other hand, is completely misleading, since both Egypt and other cultures already had an extensive literature and advanced scribal traditions 4,000 years ago!

This does not necessarily mean that there are no divinely engendered messages or hidden esoteric statements in the Tanakh as we now have it. There are certainly esoteric messages in it. Here is one example: According to Ralston Skinner, the narrative describing the famous Temple of Solomon (the «first» temple), which archaeologists have found no trace of in Jerusalem, actually encodes, in a most ingenious way, the measurements of the very real ancient architectural marvel known to us today as the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Attached is a table from Gesenius’ Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament Scriptures, as edited and translated by Samuel Prideaux Trigelles, and published in New York and London in 1889.

From the foreword: The following work is a translation of the ‘Lexicon Manuale Hebraicum et Chaldaicum in Veteris Testamenti Libros,” of Dr. WILLIAM GESENIUS, late Professor at Halle.

«The attainments of Gesenius in Oriental literature are well known. This is not the place to dwell on them; it is more to our purpose to notice his lexicographical labours in the Hebrew language: this will inform the reader as to the original of the present work, and also what has been undertaken by the translator.

His first work in this department was the Hebraisch-deutsches Handworterbuch des Alten Testaments,” 2 vols. 8vo., Leipzig, 1810-12.

Next appeared the Neues Hebraisch-deutsches Handworterbuch; ein fur Schulen ungearbeiteter Auszug,” etc., 8vo., Leipzig, 1815.

Of this work a greatly-improved edition was published at Leipzig in 1823. Prefixed to it there is an Essay on the Sources of Hebrew Lexicography, to which Gesenius refers in others of his works.

Another and yet further improved edition appeared in 1828.»

The Victorians were no fools, you see, and many of the scholars of the 1800s were more widely read and achieved greater feats of scholarship than the average academic of today, and they tended to adhere to the highest standards of academic excellence, and often boldly went where no one had gone before.

E.S.

This post was originally published on my profile at Academia.edu back in October 2024.