As many are aware of, the Old Testament or the Tanakh (including the Torah) sets forth the extraordinary claim, accepted by traditional “Judaisms” and “Christianities”, that the “Israelites” spent some 400 years in Egypt – many of them as slaves. (Genesis 15:12–14 (“four hundred years”), Exodus 12:39–41 (“four hundred and thirty years”, c.f. Genesis 11:17), Acts 7:4–8 (“four hundred years”, c.f. Galatians 3:17), etc., Exodus 1:11–14 (“Therefore they set taskmasters over them, to afflict them (…)”, “And they made their lives bitter with hard labor (…)” etc.))

“Now the sojourn of the Sons of Israel, who lived in Egypt [some ancient texts have ‘Egypt and Canaan’], was four hundred and thirty years. And it came to pass, at the end of four hundred and thirty years, it came to pass, on the very same day, that all the armies [‘tsivoth’, from tsava, army or organized host; military connotations (!)] of YHWH came out of the Land of Egypt [me-erets mitsrayim’].” (Exodus 12:40–41)

Now, if we assume that there was an Exodus of some sort, whatever its actual historical form, and that it took place at the later of the two periods usually propounded by Biblical scholars and historians, i.e. in the 1200s B.C. (the 1220s, to be more specific), the “Israelites” would, even according to this late dating of the Exodus, have been in “Goshen”, i.e. in the eastern Nile Delta, when the Expulsion of the Hyksos or Amu/Aamu, which was certainly a real, historical event, took place, i.e. in the 1500s B.C. (since the “Israelites” supposedly spent four hundred years in Egypt), and it is simply unthinkable (!), knowing what we now know of the intense animosity between the Theban Egyptians and the Hyksos (c.f. the First and the Second Kamose Stela, the autobiography of Ahmose, Son of Ebana, and Queen Hatshepsut’s commemorative inscription at Speos Artemidos, for example), that the former would have allowed a huge population (“about six hundred thousand men on foot, besides children”, according to Exodus 12:37 (there is no mention of “women” in the actual “Hebrew” text here, it seems)) of what they, the native Egyptians, would have viewed as the same type of people as the Hyksos to remain in the Delta while the Hyksos were being chased out, or forced to depart for Palestine (and the second Hyksos stronghold of Sharuhen).

(C.f. also Exodus 1:20, where it is said that “Therefore Elohim dealt well with the midwives, and multiplied the people (‘ha-am’; the ‘Israelites’ or ‘Hebrews’), and they grew exceedingly powerful (‘meoth’) (or numerous)”.)

The Hyksos were, after all, Western Semites (as the ongoing excavations of the ancient city of Avaris, and the reports published by Prof. Manfred Bietak and others, have demonstrated beyond the shadow of a doubt), just as the alleged “Israelites” were (according to conventional history), and the Egyptians undoubtedly would have viewed them as belonging to the same ethnic category.

Moreover, even if one chooses to go with the earlier of the two conventional dates for the departure of the “Israelites” from Egypt, i.e. the 1400s B.C. (the 1440s, to be more specific), the same impossible overlap of one period with another which is wholly incompatible with it results – the “Israelites” would have been in “Goshen” (or the eastern part of Lower Egypt), and therefore, necessarily, in or near Avaris, at the very time when the terrible wars between the Amu/Aamu or “Asiatics” and the Theban Egyptians took place (i.e. during the reign of King Seqenenre Tao, and of his son, King Kamose, and of the brother of Kamose, Ahmose I – or a large portion of the 1500s B.C.), and it is, again, simply unthinkable (!) that such a huge population of Western Semites as the “Israelites” (of the Biblical narrative, and of supposed history) would have constituted (hundreds of thousands) would not have first been embroiled in these wars and then have been thrown out (or compelled to leave) along with their ethnic brethren, the Hyksos.

(Note: As Prof. Manfred Bietak has repeatedly pointed out, the term “Hyksos” is, strictly speaking, only a reference to the “Canaanite” or Western Semitic rulers (!) based in the Nile Delta themselves (as opposed to the general population of “Canaanites” or Semites living there), and only means, in the original Egyptian (later corrupted), something like “Rulers of Foreign Lands” – and not “Shepherds” or “Shepherd Kings” (as Titus Flavius Josephus and Manetho both appear to have thought), but in everyday parlance, the term “Hyksos” has, nevertheless, come to refer to the Semitic or Amu population residing in Avaris, and in the rest of Lower Egypt, as a whole, and the term “Asiatics” seems even less appropriate than “Hyksos”, since the Egyptian term Amu, of which “Asiatics” is one possible translation into English, certainly refers to the “Canaanite” or Semitic or “Proto-Phoenician” (as one might say) population originating in or resident in “Palestine”/Retenu/Retjenu/”(Wider) Syria”, and not to populations further east or further north, or to “Asians” in general.

Moreover, it should not be ignored that the Egyptian hieroglyph for heqat or ruler is a shepherd’s crook or staff – of the very same kind, visually speaking, as the one Christian bishops (including the Pope of Rome) can still be seen brandishing, by the way – and it is not difficult to see, therefore, how the both the hieroglyphs for “Hyksos” and the term itself may, over the course of centuries, have come to be interpreted by an increasingly confused posterity (in Egypt and abroad) as denoting “Shepherds” or “Shepherd Kings” – particularly in light of the fact that the Hyksos had come from a region famous for shepherding, that these Hyksos had “vagabonds” or “nomads” (possibly some of the rather mysterious “Apiru” or “Habiru”, who may perhaps be more or less identical to the “Sutians” of ancient Mesopotamian records; c.f. Amar Annus article “Sons of Seth and the South Wind” (2018)) in their midst (c.f. the Speos Artemidos inscription) and that the narratives of the Old Testament or Tanakh, whenever they were given their final forms (many now suspect that to have taken place in the metropolis of Alexandria, in Egypt, in the 200s B.C.), portrayed the ancestors of the “Israelites” as precisely shepherds or nomads (narratives to which Manetho is perhaps referring when he says, in one of the precious few excerpts from his once extensive works preserved by Josephus (cf. Contra Apionem), “That this nation [the Hyksos] thus called shepherds, were also called captives in their sacred books.”).

The Theban Egyptians were, after all, seething with rage, a rage directed squarely at the Amu (the “Asiatics” from Retenu/Retjenu or “Palestine”), after the long conflict and the many years of what they viewed as a destructive and humiliating occupation or domination of their country (as their testimonies make clear), and they would certainly not have allowed very many, let alone hundreds of thousands of “Asiatics” resembling the Hyksos to remain in the Delta – not even as laborers or slaves. (The reason should be obvious – a large residual population of Amu would have constituted a terrible danger to the new unity and independence of Egypt ushered in by Ahmose I.)

Hence, we are left with the following possibilities: Either the “Israelites” of the Torah and the Tanakh were never in Egypt at all, ever, and the Book of Exodus is pure fiction (which is indeed what some scholars are maintaining), or they spent much less time there than the Biblical/”Mosaic” narrative claims that they did, and were granted free entry into Egypt at a time when the Hyksos occupation of the country would still have been vividly remembered (in which case it would have to be said that the Egyptians made a rather strange decision), or they (the “Israelites”) were more or less identical to the Hyksos/Amu, and were expelled, and went on their legendary Exodus when the Hyksos were expelled and went on their “Exodus”, as ancient authors like Josephus and Manetho and Apion and Ptolomy of Mendes in fact claimed that they did – meaning that the two Exoduses are one and the same event, involving the same people, and that the “Israelites” of real history are indistinguishable from the Amu (who are also called the Setyu on the First Kamose Stela, presumably because of their devotion to Seth) of Avaris.

If the third scenario be the true one, then we may say that the Exodus – the actual Exodus of real history, not the highly polemical and heavily romanticized Exodus of the Torah – took place in the 1500s B.C., when the Hyksos ruler Khamudi/Chamudi (also known as Assis/Aseth (Josephus), and Archles (Africanus)), son of King Apophis/Apepi (?), was – or had been – king of Avaris and of “Goshen” (for c. a decade, c.f. the notes on the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus), and when the Theban Egyptian king Ahmose (soon to be pharaoh of a United Egypt), son of Seqenenre, King of Thebes, at last achieved the dreamed-of conquest of the “Capital of the Hyksos”, i.e. between the 18th and the 22nd year of his reign (Bourriau, 1997, p. 159), which lasted for a total of 25 years.

According to the conventional chronologies and estimates, the Exodus of real history, i.e. the mass emigration of the Amu from the Egyptian Delta and (back) into “Canaan”, would then have taken place in or around 1540 B.C. (possibly a little earlier or later; there is no perfect consensus as regards the question of precisely when the various Egyptian pharaohs and Hyksos kings ruled).

Some have speculated that Khamudi is in fact the same person as the famous “Phoenician” known to the Greeks as Cadmus, but that is another story for another time.

It would be very interesting to hear what Bethsheba Ashe thinks of the thesis and the dilemma outlined above, particularly considering what her research into the hidden Gematria of the “Old Testament” would seem to reveal regarding the age, the authenticity and the messages of at least parts of that collection of ancient texts. If at least some of the “Proto-Israelites” – or maybe we should just say “Israelites” – are in fact identical to the Amu of Egyptian records, and to their “Hyksos” kings or emperors – a conclusion which, in my view, seems virtually inescapable at this point – then how might this historical reality be reconciled with what the cryptography research is revealing?

I would also appreciate Martin Euser’s thoughts on all this, since he has read not only what Madame Blavatsky stated with regard to questions such as these some 150 years ago, but also Ralston Skinner’s allegedly seminal work on “the Hebrew-Egyptian Mystery” (and Skinner’s view of the real or deeper meaning of the “Temple of Solomon”-narrative).

Edmund Schilvold

February 2025

—————————————————————————————————————-

Bibliography

Annus, Amar. (2018). Sons of Seth and the South Wind. In Strahil V. Panayotov and Luděk Vacín (Eds.), Mesopotamian Medicine and Magic, volume 14, pp. 9–24. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill. Retrieved from https://brill.com/display/book/edcoll/9789004368088/BP000002.xml

Bietak, Manfred. (1996). Avaris: Capital of the Hyksos: Recent Excavations at Tell el-Dab’a [eBook]. London, the United Kingdom: British Museum Press. Retrieved from www.academia.edu/10071070/Avaris_Capital_of_the_Hyksos

Bourriau, Janine. (1997). Beyond Avaris: The Second Intermediate Period in Egypt outside the Eastern Delta. In Eliezer D. Oren, (Ed.), The Hyksos: New Historical and Archaeological Perspectives, pp. 159–182. Philadelphia, PA, the United States: The University of Pennsylvania, The University Museum

Plato. (2000). Timaeus (Donald J. Zeyl, Trans.) [Kindle Edition]. Indianapolis, IN, the United States: Hackett Publishing Company.

Pleyte, Willem. (1862). La religion des pré-Israélites [the Religion of the Proto-Israelites]: recherches sur le dieu Seth [Research on the Deity of Seth]. Utrecht, Netherlands: T. de Bruyn

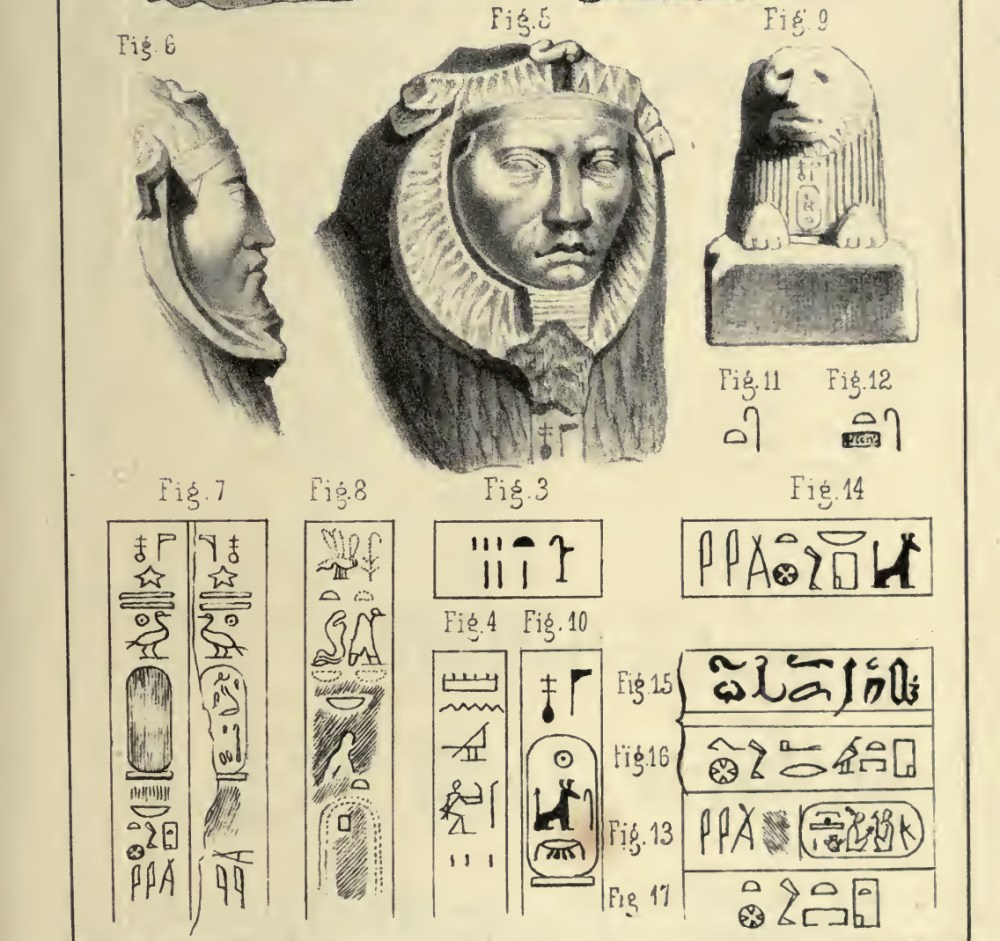

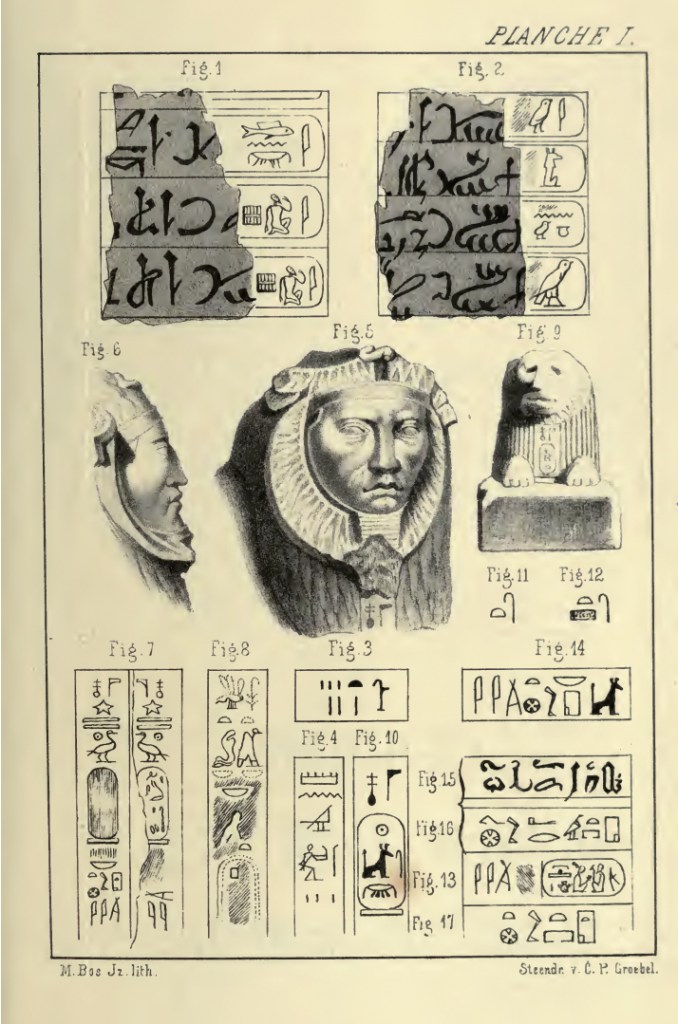

BELOW: Pleyte’s first planche or page of images (featuring that rather curious and probably not very «Egyptian» face):

Here is the legend for the «planche» or plate displayed above:

The original French text was translated into English with the aid of Google Translate

Fig. 1. Fragment no. 112 of the Royal papyrus of Turin, drawing after the Königsbuch of M. Lepsius with the correction of M. Devéria in the Revue Archéologique of the month of October p. 249, 1861.

{https://www.ancientegyptfoundation.org/richard-lepsius.shtml}

We find on this fragment the remains of four names of Kings in hieratic characters.

We have added the transcription in hieroglyphic signs.

The first name is completely illegible.

In the cartouche of the name that follows, we notice the signs a. an. n. nub, which we read: An nub or Ann? …

The third name gives the signs a. p. and a kneeling man.

These are the first characters of the name Apachnas. {This is one of the “Hyksos” or Amu rulers.}

The last contains the same signs as the third and we find there the initials of the name Apépi. {This is the famous “Hyksos” or Amu ruler, who allegedly reigned over both Lower and Upper Egypt for several decades.}

Fig. 2. A fragment of the same papyrus is fragment no. 150. It presents us with four names of kings in hieratic writing; the transcription in hieroglyphic signs is added. Drawing after M. Lepsius.

The names are unknown. It is only because we find the sign of Set in the second name, that we suppose that the fragment mentions the reign of the Hyksos.

Fig. 3. Hieroglyphic group according to the Zeitsch. of the D. M. G. 1855, p. 211.

The upper signs belong to the sign of t. Two of them must be omitted; the three signs below mark the number of the year. The hieroglyphic sign that signifies the year is found in front of the group.

Fig. 4. Hieroglyphic group according to the mentioned Zeitsch, fig. 3. It presents the phonetic signs M. n. a. Mena, Egyptian name meaning shepherd.

Below we find the pillory, a sign used, as well as the sign that follows the plowing man, to designate peoples in slavery or despised.

The three small lines even lower down, signify the plural.

Fig. 5. Drawing according to the Archaeological Review of February 1861.

It represents the sphinx of Sân {or Tân/Tsân/Tanis}.

Fig. 6. See fig. 5, the same in profile.

Fig. 7. Inscription in two columns, according to the Archaeological Review of October 1851, page 249.

In the first column we discern the signs:

Nuter-nofre-siu-to, ti-se-Ra

God, good, star, of the two worlds, son of Ra.

Under the royal cartouche, which no longer contains signs, the figure of Set or Sutech is erased. The signs that remain are:

Neb-Tan-meri.

(of) the Lord, of Tân, the beloved.

The second register presents the same signs but in the royal cartouche we can still read the remains of the signs Set or Sutech, t and i, which combined give the name of Sutechti.

The restored legend, equal on both columns would read as follows:

Nuter-nofre-siu-to, ti-se-Ra-Sutechti.

God, good, star, of the two worlds, son, of Ra, Sutechti.

Sutech-neb-Tan-meri.

of Sutech, the lord, of Tân, the beloved.

Fig. 8. Inscription found on the Sphinx no. 23 of the Louvre published in the Revue Archéologique 1861, October, p. 249. — The first two signs designate the dignity of a King, the Uraeus combined with the vulture, placed on the signs which designate the power or the government, signify:

King of Upper and Lower Egypt. The other signs are completely erased, except the sign of the P. in the royal cartouche, placed in the same place, as we find it in the name of King Apepi.

Fig. 9. Sphinx according to the drawing in the Revue Archéologique, see the explanation of fig. 8, found in Baghdad, of which we speak in the inscription fig. 10.

Fig. 10. Inscription of the Sphinx of Baghdad representing the signs:

Nuter-nofre-and the Royal name–Ra-s-set or sutech-nub

God, good, Ra Set nub.

The sign S is probably used instead of the group fig. 11 or the group fig. 12.

Fig. 11. Hieroglyphic group giving the signs s. t. used for the name of the god Set.

Fig. 12. The same characters, or phonetic signs, with the determinative sign, the stone, whose Egyptian name is Set.

Fig. 13. Drawing after the Revue Archéologique 1861 February. Name of a king on the base of the Sphinx of San. The sign of Sutech or Set is mutilated – it is the name of Menepthah II:

Mei-Ra-Ma n-hotep-het-Sutech-meri.

The beloved of Sutech.

Fig. 14. Drawing from the Zeitsch. fig. 3 Inscription of the colossus of Ramses II in Berlin; hieroglyphic group giving the signs:

Sutech-neb tan-meri.

of Sutech, the lord, of Tan, the beloved.

Fig. 15. Hieratic group; we have added the transcription in hieroglyphic signs.

Fig. 16. From the drawing by Mr. Brugsch in the Zeitsch. mentioned in fig. 3.

The first sign is the phonetic m, the second is the figurative signifying habitation.

The next two are the determinatives of the second sign.

Then we find the phonetic u. a. r and the sign tan followed by the two legs, used after verbs signifying to walk.

The last sign is used to indicate a country or city. The whole group reads:

M-ha-uar-tan.

In, Haüar, Tân.

The sign tan is the Semitic name of Tanis, identical with Tsanis, Tsân or Sân.

The Egyptian translation of this word is Uar, which means departure.

It is probable that the Semitic name of the city was introduced by chance, in the Egyptian name.

Fig. 17. Hieroglyphic group, the name of the city of Tan see Champollion, Dictionary of Egypt, page 116.

The plate itself is found on p. 257.

The legend for that plate is found on pp. 242–244.

Please note: When Willem Pleyte composed his ground-breaking work on the religion of the «Proto-Israelites», many archaeologists were still of the opinion that it was Tan or San or Tanis which had been the «capital» and power base of the Hyksos while they were in Egypt. It is my understanding that proper excavations of Avaris («Tell el-Dab’a») had not yet begun back then, even though several pioneering European researchers were probably aware of the location. One of the differences between Tanis and Avaris is that the latter is found significantly further to the east, right next to the now extinct Pelusiac branch of the Nile river, in the middle of the region the Torah styles «Goshen», and very, very close to the later urban development known as Rameses or Ramesses or Pi-Ramesses.

Avaris is, moreover, not very far away from the unusual piece of geography connecting the eastern Nile Delta to the Sinai Desert and «Canaan», and this border region includes, as I recently found out while reading Strabo, the geographer, a strange, very long and very narrow land bridge between the huge delta lake Sirbonis and the Mediterranean sea — a land bridge which I now find myself unable to study without thinking of the famous «parting of the waters» supposedly carried out by «Moses». It is conceivable that this bizarre sliver of land, or something resembling it, was already present back in the 1500s B.C., that it increased and decreased with the rhythm of the tides of the Mediterranean, and that it would have constituted the only comparatively safe and comfortable route between Avaris/Ramesses/Goshen and «Canaan»/Retjenu/»Palestine», and between Avaris and the second fortified city of the «Hyksos» or Amu, namely Sharuhen, the stronghold which the Hyksos reportedly fled or migrated to when Pharaoh Ahmose I forced them to abandon Avaris.

Avaris was not only a city with huge walls, temples and gardens, by the way — it was also a thriving port city, as the Second Kamose Stela makes clear, and it does not seem unlikely that some of the Hyksos or Amu, who were manifestly in touch with the «Phoenicians» or «Proto-Phoenicians» of the Levant, if not actually a branch of the «Phoenicians» themselves, would have fled Avaris by way of the sort of ships mentioned by King Kamose. Perhaps some of them eventually wound up in Greece.

Centuries later, the above mentioned city of Tan or Tanis, also known as San and Zoan (>>> «Zion»?), would become the powerbase of another strange and mysterious dynasty, possibly also of foreign origin, which must have been exceedingly wealthy:

For more on the wars between the Theban Egyptians and the Hyksos, see my profile page on Academia.edu: https://vid.academia.edu/EdmundSchilvold

This profile page is the real and authentic one.